Image Caption

Summary

Windspeaker.com Contributor

First Nations in Alberta are armed with statistics that will aid in their fight against drug abuse and misuse in their communities.

“Figures (like these) aren’t available anywhere else in the world, except for Alberta, Canada,” said Bonnie Healy, executive director with the Alberta First Nations Information Governance Centre.

And they are only available because five years ago, Blood Tribe Chief Charles Weasel Head needed to get a grasp on the figures after declaring an opioid crisis on his reserve.

“What Chief Weasel Head was worried about was that it was killing his people,” said Healy.

Healy was surprised to learn that the data Weasel Head was requesting was not readily available. Having been an emergency room, trauma-trained nurse, she knew that a detailed toxicology panel was drawn from every overdose fatality. However, like every other medical examiners’ office both nationally and internationally, Alberta only coded the deaths as opioid-related. Using the data from the medical examiner’s office and Alberta Health, Healy recoded the data over a two-year period.

What she found was disturbing.

“This isn’t simply just an opioid crisis. This is complex because there are multiple things. They’re not just on fentanyl,” she said.

The majority of people who died were on a prescribed hydromorphone.

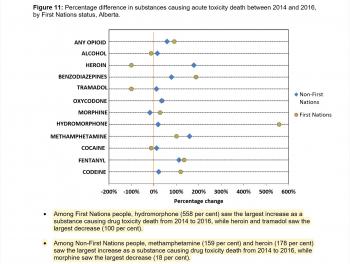

Hydromorphone, at 558 per cent, saw the largest increase as a deadly drug substance in First Nations’ overdose deaths. That finding “startled” Healy, as hydromorphone, a very strong opioid used to combat extreme pain, must be prescribed by a physician. However, she says, like other opioids, like fentanyl and carfentanil, hydromorphone can be sold on the street.

Fentanyl also saw an increase of about 150 per cent and benzodiazepines of about 100 per cent, while heroin and tramadol decreased by 100 per cent and cocaine stayed steady.

In comparison, hydromorphone saw only a slight increase as the cause for overdose deaths for non-First Nations Albertans.

“We have to address the prescribing practises,” said Healy.

It’s a complicated issue, she admits. It would involve detailed research including interviewing the prescribing physicians, reviewing their charts and checking their diagnoses.

“What most likely happened is if they don’t know what causes the source of pain, they’d write NYD, not yet diagnosed, but they’ll continue to prescribe for pain management. The problem is the length of referral to get a diagnosis for what is causing the source of pain,” said Healy.

Detailed diagnoses require “expensive investigations” and long waits for referrals. While Non-Insured Health Benefits cover costs, complications arise from the distance First Nations people have to travel to reach specialists, lack of language and cultural consideration, and child care issues.

“We support the nations with the data they need to evaluate and measure indicators to see where they need to set their priorities with some of the programs they’re providing,” said Healy.

“They need (data on) everything. We’ve just heavily leaned on the health data, which is a start, but they need their education data, their justice data, their child welfare data.”

Healy says the First Nations Information Governance Centre is presently collecting updated mortality data from opioid-related deaths for a second report. The most recent information available to chiefs was given to them in a November 2017 report, a collaboration between the centre and Alberta Health, that collected and analyzed data from 2013-2017.

“The data is very difficult to look at … it’s about healing families and having the resources to do that,” she said.