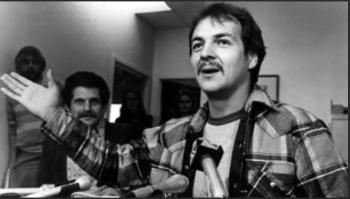

Image Caption

Summary

By Paul Barnsley, Windspeaker Writer, September 1999

On Sept. 17, 1999, convictions against Donald Marshall, Jr. for illegal fishing were erased when the Supreme Court of Canada rendered its decision.

Five of the seven justices who considered the case agreed that Marshall had a treaty right to do what he was charged with by department of Fisheries and Oceans officials: catching and selling 210 kg (463 lb) of eels with a prohibited net outside of the fishing season.

Supreme Court Justice Ian Binnie wrote the majority decision for the court.

"The only issue at trial was whether he possessed a treaty right to catch and sell fish under the treaties of 1760-61 that exempted him from compliance with the regulations," Binnie wrote.

In the end, the court decided Marshall did have that right.

While Native leaders in the Maritimes were delighted and National Chief Phil Fontaine applauded the decision, Bruce Wildsmith, the Barss Corner, N. S. lawyer who represented Marshall in front of Canada's court of last resort, cautioned the decision is, for the most part, a decision that effected only East Coast Aboriginal people.

"The Marshall decision is based on a series of treaties that were made here," Wildsmith told Windspeaker on Sept. 21, 1999.

"So, it's pretty hard to say that people who are not beneficiaries of those treaties would have the same rights. I hate to be a wet blanket about that, but I think the reality is that these treaties are unique."

But all Indigenous peoples who signed the 1760-61 treaties have been recognized as having a constitutionally-protected right to fish commercially for, as it was stated in the treaty, "necessaries."

The court interpreted that to mean the treaty allows Aboriginal people to harvest the resource and engage in commercial activity that provides "a moderate livelihood."

"Those treaties are encompassing all of the Mi'kmaq and Maliseet and Passamaquody Indians which would encompass all of the Aboriginal people in all of three provinces and pieces of two others. So it's all of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, plus the Gaspé area of Quebec and the south coast of Newfoundland," Wildsmith said.

National Chief Fontaine sees a carry-over effect from this decision that will help all First Nations in the country.

"The Supreme Court decision vindicates Donald Marshall and all other First Nations citizens by recognizing what we have said all along: our treaty rights recognize our right to harvest, in this case fishing, and to sell the catch to provide for ourselves and our families. The court has also recognized our oral history which has always claimed the treaties had a wider context than the written word," Fontaine said.

Wildsmith believes the court has added to the body of Aboriginal case law, but he believes his client's people will see most of the benefits of this decision.

"The court did a better job than any other case to this point in time in summing up how you go about the process of interpreting treaties. And, in particular, one of the loose ends that had been left by earlier treaty cases is whether there needs to be some kind of ambiguity in the formal document itself before you can look at surrounding negotiations, discussions and context. They clarified quite directly that there was no problem in the absence of ambiguity to look more broadly to see, for example, if all of the promises had been written into the text," he said.

The court overturned the lower court decision, saying the court erred in not allowing extrinsic evidence—evidence which clarifies a contract that is outside of, or not part of, the actual contract. When that contract is an Indian treaty, Wildsmith said, the court ruled the honor of the Crown requires that all evidence that can help in getting the proper interpretation must be considered.

For more on this story, go to the story on our archives site at https://ammsa.com/publications/windspeaker/fishing-charges-overturned-0