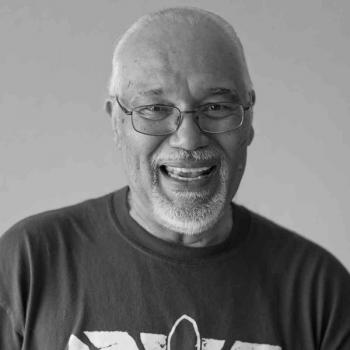

Image Caption

Summary

Windspeaker.com Archives

Fans of comedian Charlie Hill wished him a good journey into the spirit world and imagined the impact of his razor-wit on ‘the other side’.

“Nelson Mandela has a front row seat at Charlie’s first stand-up show in heaven” posted one Facebook supporter, while another claimed “God is slapping his knee at Charlie’s jokes as we speak.”

Here on earth, signage in front of the famous Laugh Factory in Los Angeles where the comic often performed read “Charlie Hill, Rest in Peace, Make God Laugh”.

Designing the blueprint for today’s Indigenous comedians, the comedy legend remained one of the best over his decades-long career. Battling lymphoma cancer for a year, he succumbed to it on Dec. 30, 2013.

“He broke all the barriers,” said Winnipeg comedian Don Burnstick, 18 years in the business himself. “I think there’s about 60 of us out there doing (Aboriginal) comedy now and it if wasn’t for Charlie Hill, we wouldn’t have a career.”

“Just like Redd Fox and Richard Pryor did for Black people, Hill did for Indian people. Charlie hung out in Los Angeles in the early days with guys like Pryor, who was so ‘on the line’ and ahead of his time … well, it doesn’t get any better than that.”

As a kid growing up in Oneida, Wisconsin, Hill wrote down the jokes of classic television comedians like Jackie Gleason and Red Skelton. Hitting Los Angeles in the mid-seventies, he watched other stand-ups perform before eventually stepping onto the stage himself.

He impressed Richard Pryor enough to be invited to guest on the top entertainer’s show in 1977. In iconic footage from The Richard Pryor Show, a slight, innocent-looking Hill with long, wavy hair, slings zingers like ‘I’m Oneida … we’re originally from New York, but there was a real estate problem’ and ‘I know for a long time you White people didn’t think Indians had a sense of humour. Well, we didn’t think you were too funny either.’

Hill once told an interviewer that Pryor advised ‘whatever hurts you the most, talk about it and it’ll be your funniest comedy’. Encouraged, the protégé merrily attacked the racial divide with insightful, autobiographic jokes to make his audiences think, all the while laughing out loud.

“What I do, I don’t really call ‘Indian humor’,” Hill said, quoted on the Native-Arts Live Journal website. “It’s more of a satire. Real Indian humour is something in your community or your home, and the funniest people are maybe your uncle, or a cab driver, or someone on the rez. It’s something only people with Indian experience get. It’s something that’s personal to us. It’s something beautiful. Often, I don’t like guys who get off-stage and you know nothing about them. You watch Cosby, you learn something about him.”

Hill became the darling of television programs like The Tonight Show, Late Night with David Letterman and Merv Griffin. He also wrote for the hit television show Roseanne.

He turned down many roles, standing up against stereotypes and misrepresentation of Aboriginal people.

“Charlie was instrumental in breaking down stereotypes and cultural misnomers about Native Americans in the national spotlight,” wrote Ernest L. Stevens, chairman of the National Indian Gaming Association in Washington D.C. His letter appears on the EverRibbon website where The Charlie Hill Fund had been set up to receive donations to help the family offset medical expenses.

“We honour Charlie’s memory … He was always there for us, taking us to a better, happier place, interrupting the mundane and historical bitterness through his comedy. He taught us to heal our generational trauma through the medicine of smiles, belly laughs and humorous insights,” Stevens’ letter read.

He also shed light on Hill’s efforts to empower Native Americans to take their place in the entertainment industry, and that he “carved a path for Native artists and entertainers throughout the Indian gaming industry (in the United States), advocating for the hiring of Indians in Indian casinos and expanding Native-to-Native business relationships.”

The funny man called Winnipeg his second home, according to Winnipeg Free Press columnist Don Marks. Marks, who was the producer of the CTV variety show Indian Time, which featured Hill and the likes of Buffy Sainte-Marie, Kashtin, and Tom Jackson, recalled Charlie’s parting lines when it was time to leave. ‘I’m off to New York, Chicago and Los Angeles, and if I can’t find work there, I’ll be back here’.

“Charlie’s gift of laughter to Winnipeg … had healing powers,” Marks wrote. When humor is combined with insight and enlightenment, it “allows us to laugh at ourselves and others in a spirit of camaraderie and friendship that breaks down barriers. With the way things are between First Nations people and many Canadians, we could use Charlie Hill more than ever.”

Hill disliked leaving his wife and four children (whom he referred to as ‘Oneida-ho’s because their mother is Navajo) preferring to commute from Wisconsin to Los Angeles for work. Marks wrote that Hill was generous with his time when it came to charity fundraisers, though, traveling to even the smallest of communities to help.

Because of the disproportionate representation of Aboriginal people in jails, he also devoted much of his time to performing in penitentiaries, joking that he did so because he enjoyed a “captive audience”.

Marks had the chance to speak with Hill as cancer took its toll. The comedian said he was not afraid to die but was “going to miss my family and friends a lot.”

“Not as much as we’ll miss him,” Marks concluded, speaking for many.