Image Caption

By Dianne Meili

Windspeaker.com Archives, 2016

One cold winter night, Larry Loyie and his younger sisters hauled an old steamer trunk up Rabbit Hill overlooking Alberta’s Slave Lake. Unable to afford a real sled, a scoop shovel and tin strips served as sled runners as the children hopped into the box to fly over the snow.

It’s scenes like this, simply and honestly told, that engaged readers, young and old alike, in Loyie’s books. His Cree upbringing was first captured in “As Long as the Rivers Flow”; its success paved the way for three more books detailing his early life.

His sledding adventure in “The Moon Speaks Cree”, the fourth and final installment in his award-winning Lawrence Series, captures the closeness of traditional Aboriginal life in the early 1940s, and shares deeper lessons of respect for culture and history.

The former residential school student never forgot his dream of being a writer, even as he held down jobs in logging camps and in commercial fishing on the West Coast. He taught himself to type and went back to school in the mid-1980s to learn grammar. He took a free creative writing course at an east Vancouver learning centre.

He published short pieces and was soon deeply involved in the Canadian literacy movement, co-editing

“The Wind Cannot Read”, an anthology of learners’ writings published in B.C. for 1991’s Year of Literacy.

“He was already well on his way to becoming a full-time writer when we met,” said Constance Brissenden, who taught creative writing at the learning centre Loyie attended.

The University of Alberta theatre graduate directed Loyie’s first play “Ora Pro Nobis, Pray For Us”, based on his years in residential school, a subject that was only just beginning to be talked about.

After three more plays, Loyie focused on children’s books to help readers, especially young Aboriginal students, understand the simple beauty of Indigenous culture.

By this time, he and Brissenden had become life partners and had formed the Living Tradition Writers Group, encouraging others to tell their stories. The two would spend 23 years writing together, and travelling to classrooms, libraries, conferences and festivals across Canada.

“Larry didn’t do what he did because he wanted to become a famous writer,” said Brissenden. “He wrote because he wanted children to know about the positive aspects of their culture. His culture was Aboriginal, of course, but he told all kids – Philippine, German, East Indian – to learn about their culture.”

In her tribute to her great uncle, Brookelynn Fiddler wrote “Larry Loyie is my hero because he was a spiritual speaker and he turned anything that was going well into something going great. He has taught me to always believe in my culture no matter what people may say or if they judge.”

After more than two decades of making more than 1,600 literary presentations across Canada, Brissenden confesses she was looking forward to retiring from their arduous schedule.

“When Larry was 78 I asked him about retiring. But he said ‘we’re not going to retire. I have to keep doing this for the children. I need to encourage them to feel pride in their culture and who they are.”

The quiet, unassuming Loyie, whose grandfather Edward Twin gave him the Cree name Oskiniko – Young Man – was born in Slave Lake in 1933.

His life in the bush was spent helping his family with daily chores like gathering wood and carrying water, punctuated with teachings from his grandparents and adventures like the one he shared with his Kokom (grandmother) Bella Twin.

In “As Long as the Rivers Flow”, Loyie describes a medicine-picking trip with Bella that could have ended with a bear attack. A grizzly bear unexpectedly reared up before them on the trail but Bella handily shoots it with her old .22 rifle. The skull of the biggest grizzly bear in North America is housed in a private museum near Slave Lake, and his grandmother’s prowess with a gun is still talked about amongst hunters.

After three years in Slave Lake public school, Loyie spent three years in Grouard’s St. Bernard Mission. He was allowed to return home for two months every summer.

When a fever sends Loyie to the High Prairie hospital, the young boy enjoys time away from the oppressive school and flips through a “Look magazine” featuring an article about bullfighting by Ernest Hemingway.

Admiring the photos of the writer watching a bullfight with glamourous women–and more photos in the magazine of mountains and rivers–he decides then and there to be a writer and to travel to faraway countries.

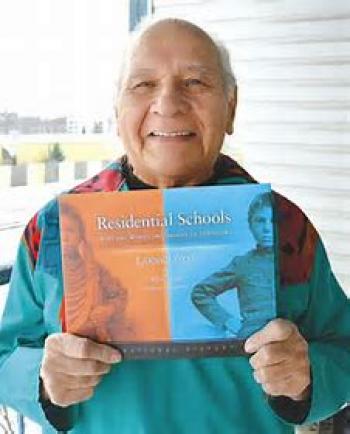

After leaving school at 14, Loyie would spend years working as a labourer until acting on his dream and taking his first writing course. His distinguished career culminated with the publishing of “Residential Schools, With the Words and Images of Survivors” in 2014. The full-colour, hard cover book was written with Mohawk writer and residential school expert Wayne K. Spear, and features many of the over 200 interviews Loyie and Brissenden conducted with survivors over 20 years.

First person accounts outline the strict military model the schools followed, the endless hours spent in church praying, and how hard work in the fields replaced learning in the classrooms, at least in the early years.

“It’s his masterpiece,” said Brissenden. “Since it came out it’s already sold over 7,000 copies. That’s huge. 1,200 copies is a Canadian bestseller. It’s being used in schools across Canada and its being reviewed to be used in the new residential school curriculum.

“As Long as the Rivers Flow came out in 2002 and it’s still a bestseller. It’s spent 14 years on the publisher’s list.”

Loyie was diagnosed with cancer in 2010. Sick for six years, he began using technology like Skyping to reach his audiences, but continued with interviews and appearances as best he could.

He passed away at 82 in Edmonton on April 18, 2016.