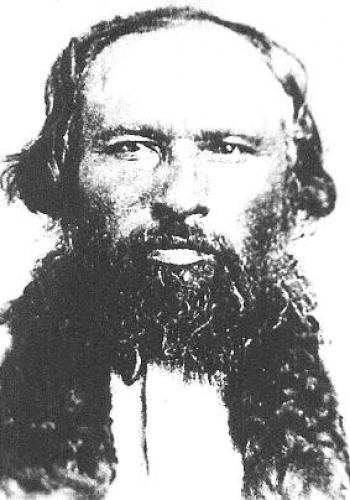

Image Caption

Cheryl Petten

Windspeaker.com Archives

When most people think about the Northwest Rebellion of 1885, the first name that pops into their minds is Louis Riel. Fewer people think of the man who stood by Riel's side, commanding a handful of Métis men willing to fight to protect their way of life. That man was Gabriel Dumont.

Dumont was born in St. Boniface in December 1837, near present-day Winnipeg. He was the fifth child born to Isidore Dumont and Louis Laframboise, the daughter of a Métis hunter.

His grandfather, Jean-Baptiste Dumont, had been a voyageur from Montreal, employed by the Hudson’s Bay Co. His grandmother was a member of the Sarcee (Tsuut'ina) Nation.

Throughout his life, Dumont was the epitome of all things Métis. He was a skilled rider, hunter and trapper, and knew the land as well as any of the Native people that lived on the western plains.

By the age of 25, he was selected as chief of the Saskatchewan buffalo hunt, and, in effect, the leader of the Saskatchewan Métis.

By this time, things were beginning to change for the Métis. The buffalo were disappearing, hunted out of existence and many Métis realized that all they would have left would be their land, so they began to take steps to protect it.

As a way to solidify their claim on the land, Dumont and others set up a permanent settlement along the Saskatchewan River, near present day Saskatoon.

Meanwhile, in the Red River colony where the Métis had years before built their houses and laid their claim to the land, trouble was brewing. In 1869, the Hudson's Bay Co., which had claimed ownership of Rupert's land—an area stretching from the Canadian Shield in the east to the Rocky Mountains in the west—transferred the land to the newly-formed Canadian government.

The government, in turn, refused to recognize the Métis claim to the land within the colony. In response, the Métis, led by Louis Riel, stopped government surveyors and formed a provisional government. The uprising eventually lead to the creation of the province of Manitoba, and a promise to provide Métis in the colony with a land base of 1.4 million acres.

But Riel was exiled from Canada for his part in the rebellion and the execution of Thomas Scott, a prisoner of the Métis who had escaped, only to be recaptured a month later. He was tried and found guilty of defying the authority of Riel's provisional government, and sentenced to death.

Learning from the experience of the Red River Métis, Dumont and the men he led set up more permanent settlements in St. Laurent and Batoche. Dumont built a house and a store, and began running a ferry service across the Saskatchewan River at a point that came to be known as Gabriel's Crossing.

As the buffalo dwindled, and the communities grew, the question of land guarantees for the Métis of Saskatchewan became a priority. In 1878, they sent a petition to the government asking that the land occupied by Métis people be surveyed and title granted to them.

Rather than address the concerns of the Métis, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald chose to ignore them, despite the fact that the circumstances in Saskatchewan were so similar to those that began the rebellion in the Red River colony.

Surveyors were sent out to survey the land, but they divided it into square sections, rather than into the long, narrow riverfront lots that were the Métis way. And until the federal government ruled otherwise, every Métis living on the land was considered a squatter, with no legal claim or protection.

When their appeals to the federal government fell on deaf ears, the Métis decided to ask Riel to come to their aide. On May 19, 1884, Dumont and two others began their journey to Montana to find the exiled Riel, who returned to help them make their case to the government.

In December of that year, one last attempt was made to negotiate with the federal government. Another petition was sent to Ottawa asking for the establishment of an elected provincial government, regional representation in Ottawa, and for the land patent laws to be amended to allow for the Métis to gain ownership over their lands.

In February, a response was sent by the government, saying Cabinet would "investigate claims of half-breeds." Patience with the federal government was at an end. Both Dumont and Riel agreed it was time for action.

A provisional government was set up on March 19, with Dumont elected as head of the army. Riel took no official position. While Dumont and Riel sought the same outcome, they often disagreed about the best way to achieve that end.

As soon as his forces were organized, Dumont wanted to launch surprise attacks on Fort Carleton and the community of Prince Albert, both as a tactical move and to obtain guns and ammunition. Riel said no, and Gabriel respected his wishes.

The first battle of the rebellion, between the Métis and mounted police, came on March 26 at Duck Lake. When it ended, the Métis had emerged victorious. In Ottawa, the federal government was finally ready to address the "Métis problem" and sent the military to crush them.

Major-General Frederick Dobson Middleton arrived in Winnipeg on March 27, and set out West, gathering troops along the way.

Dumont had scouts tracking the movements of the military, and proposed that he and his men harass Middleton's troops at night, depriving them of sleep and eroding their morale. Once again, Riel said no.

"I yielded to Riel's judgement, although I was convinced that, from a humane standpoint, mine was the better plan, said Dumont about not challenging Riel. “But I had confidence in his faith and his prayers, and that God would listen to him."

Though hampered by Riel's refusal to use guerilla tactics, Dumont still claimed victory at Fish Creek when he came up against Middleton and his troops. The next battle was fought in Batoche.

The Métis saw the battle coming, and Dumont wanted to ambush Middleton's troops as they made their way to the community. But Riel said God had told him to wait until Batoche was attacked, and then defend it. Once again, Dumont was convinced his approach was the one to take, but once again, he deferred to Riel. While the Métis were strong in spirit and conviction, they were severely outmanned and outgunned. Still, they prepared for battle, melting down the lead linings of tea chests to make bullets and cutting up pieces of scrap metal for ammunition for the shotguns.

On May 8, Middleton and his troops reached Gabriel's Crossing, where they burned Dumont's house to the ground, and advanced to Batoche.

Dumont and his 300 men did more than hold their own against Middleton and his army of 850 strong. For three days the battle raged, with the military registering most of the dead.

But by the end of the third day, the Métis ammunition was all but exhausted. The men had begun loading their guns with nails and stones in order to continue the fight.

The end of the battle came on the fourth day, not through any clever military maneuver from either side, but out of the unbridled frustration of a handful of Middleton's troops, who broke rank and charged down the hill to the Métis rifle pits, flushing the men out.

The Métis withdrew into the village, where they made their final stand, but could no longer hold off the Canadian troops. The battle was over.

After the defeat at Batoche, the lives of Dumont and Riel went in separate directions, ending in separate fates. Riel surrendered to the Canadian military, was tried and found guilty of treason.

Dumont crossed over the border into the United States, where he began planning a rescue of Riel. The mounted police, taking no chance that Dumont would make an attempt, had 300 armed guards surrounding the barracks in Regina the day of Riel's execution Nov. 16, 1885.

After Riel's death, Dumont spent some time performing with Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West Show. In 1886, the Canadian government granted amnesty to anyone who had taken part in the rebellion, and two years later, Dumont returned to Canada. In 1893, he returned home to Batoche, where he died in 1906.