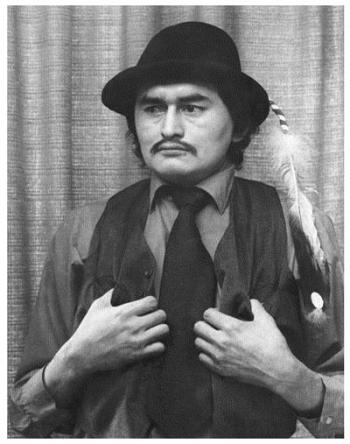

Image Caption

By Gauri Chopra

Windspeaker.com Archives

In 2006, five years after his death, Everett Soop was awarded the Meritorious Service Decoration (Civil Division) by Gov. Gen. Michaelle Jean. The award was given to 14 individuals whose work brought honour to their communities and to Canada.

Mr. Soop, who passed away Aug. 12, 2001, is remembered for his relentless quest for social justice for his people, as well as for his unique contributions to his province and his country,” read the description of Soop’s contributions on the Governor General’s Web site.

He was an advocate for Aboriginal people and physically challenged persons. Everett Soop personally suffered from muscular dystrophy, worked unselfishly for the cause of First Nations peoples living with disabilities.

His efforts during his tenure with the Alberta Premier’s Council on the Status of Persons with Disabilities culminated in 1993 with the publication of a major report entitled, Removing Barriers: An Action Plan for Aboriginal People With Disabilities.

Born in 1943 on the Blood reserve in southern Alberta, Soop spent a large part of his life as a cartoonist for the local Aboriginal newspaper, Kainai News.

Soop lived until he was 58 years old, 28 years longer than expected by doctors. He was diagnosed with muscular dystrophy at birth and his parents were told that it was unlikely he would live past his 30s. But there was no stopping Soop’s passion for life.

“I think that the world is here for us to live, and that is what I’m going to do, is live,” Soop said in Soop on Wheels, a documentary that focused on his accomplishments.

“I’m not sick, I’m disabled. There is a difference.”

The film was made in 1998, during a time when Soop’s health was failing him. He agreed to take part in the project in hopes of bringing light to issues facing Aboriginal people with disabilities.

As a young child, Soop spent a lot of time with Elders, and was very close to his grandmother. He was her favourite, and she would bring fruit for him whenever she visited. Part of that close bond came from the fact that the two shared a similar sense of humour.

Though his jokes were often snide and hurtful, Soop still had an uncanny ability to make people laugh. His satirical sense of humour was reflected in the cartoons he created. Much of his fame came from his ability to represent painful truths about society and life on the reserve through his art.

His cartoons commented on the social concerns of Aboriginal people at the time. With thick strokes from his pen, he depicted scowling faces that often represented anger, fear or injustice.

Soop was known for his ability to depict irony and truth in just a single image. Through this he was able to evoke emotion within readers. As a result, there were many fans of his work, and equally as many who didn’t it.

During his time at Kainai News, he was often accused of calling out band members in his cartoons. Needless to say, his relationship with some of them was strained.

Once, the board of the paper asked him to write an assessment of himself.

“It is quite well known to those who know me that I don’t have a pleasant personality, completely incapable of giving a ‘Good morning’ smile—until after midnight. As a matter of fact I am known as the ‘office grouch’ who takes sadistic delight in picking on the staff in turns and most often telling them what I honestly think of them, sparing them only of the most cruel thoughts, which I save as ideas for my cartoons,” he wrote.

This is who Soop truly was for much of his life.

But there was also a softer side to him, a side that he shared only with his family and close friends. He had a love of music, which he passed on to the younger generations of his family, who developed an appreciation for classical music, blues and jazz by listening along as Soop enjoyed songs from his music collection.

Soop worked at Kainai News from 1968 to 1986, drawing 2055 cartoons for the publication. But relations slowly went sour between Soop and the board of the paper, and Soop decided to leave.

His love for political satire, his interest in band issues and the popularity he gained through his cartoons lead him to run for a seat on the Blood band council. He won, but later said that it was the worst decision he had ever made.

Soop had entered into the political scene hoping to make changes, but was quickly frustrated by the lack of influence he as able to wield as a band council member. He served two terms, then decided to leave politics behind him.

He tried to return to his old job at Kainai News, but was not satisfied with the terms they offered. So he chose to remain unemployed as his health continued to deteriorate.

By this time he was 43 and confined to a wheelchair, suffering from diabetes, and recovering from a broken hip. But this didn’t stop him. He decided to shift gears and make advocating for the rights of people with disabilities his new focus. He began to travel and give talks on what it was like to live with a disability.

Near the end of his life Soop was admitted to the extended care centre on the Blood reserve. He sold many of his cartoons to the Canadian Museum of Caricature in Ottawa, and left others in the care of his trusted friend, author and historian Hugh A. Dempsey. The remainder he willed to his grand-niece.

Through his life and work, Soop awoke the fighting spirits of many Canadians—Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, disabled and able-bodied. His cartoons commented on and questioned the structure of society, and his art reflected a passion for the truth.