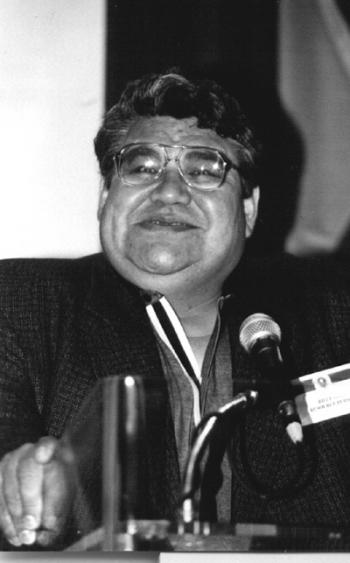

Image Caption

By Dianne Meili

Windspeaker.com Archives

When Billy Diamond was a skinny, seventeen-year-old he watched young Cree leader Robert Kanatewat tell bureaucrats that English would be the language used in the new community school to teach students, not French.

The government officials agreed with him, and the visiting Kanatewat flew out of the reserve, then known as Rupert House, but not before he’d left a lasting impression on the politician-to-be.

“He was carrying a briefcase. A briefcase in Rupert House!” recalled Billy in Chief, The Fearless Vision of Billy Diamond, a biography written about him by Roy MacGregor.

“Every eye was on him. Not because of the way he was dressed or anything, but because of the way he carried himself … so calm and so sure of himself,” Billy added. For the first time in his life, Billy saw “the kind of authority a real chief should have.”

Back in his Sault Ste. Marie high school, Billy was beginning to feel Indian pride and become politically aware. He helped set up the first Indian Students’ Council in the city and edited the group’s newspaper.

After high school, Billy returned to his community, now known as Waskaganish First Nation in Quebec, and helped his father Chief Malcolm Diamond with political affairs.

He quickly established himself as a major player in his small village, organizing grant applications, handling welfare cheques, and becoming the first resident to own a shiny new skidoo.

In 1970, at the age of 21, Billy was elected as chief of his community. A month later, eight bedraggled Cree Elders walked into his office saying they had met land surveyors in the bush who told them their magnificent lake was going to be flooded.

It was true. Premier Robert Bourassa wanted to harness the power of James Bay in a $6-billion hydroelectric project that would give Quebec economic stability and create 125,000 jobs.

Even though the Cree had hunted and trapped for more than 5,000 years along the coastal rivers, they were forgotten in development of the “project of the century.” Billy took on the government like the fighter he was, and he brought out the battling instinct in his people.

He showed trappers’ maps indicating the devastation of the flooding to their livelihoods, and began organizing meetings so the government would have to listen to a galvanized front.

In 1974 he became the first Grand Chief of the Grand Council of the Crees of Quebec and later signed one of the biggest land claim settlements in Canada – The James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement – with the provincial and federal governments.

Billy created national and international media attention to spotlight the plight of the Cree and Inuit of the north, and went to the United Nations to argue the Aboriginal case. His land claim action set a new standard for how government engaged with Aboriginal communities.

In his personal life, though, Billy was so caught up with the fight over the flooding that he barely noticed his wife Elizabeth was almost to term with her second pregnancy.

His wife wanted him home for the birth and she complained it was all she could do to care for their toddler with him away so much. He promised to be there for her – the first of many he would not keep – but arrived late to a feverish newborn and distressed mother. At the community medical clinic the parents watched helplessly as their daughter took a final shallow breath and died.

Billy didn’t have long to mourn; he took on the role of businessman and entrepreneur, as well. The Cree were awarded $136 million in cash and investment infrastructure that totalled more than $1.4 billion, and he helped establish companies that would take his impoverished community into new prosperity: Air Creebec, the Cree Construction Company, and Cree Yamaha Motors.

Billy’s next big battle came in the 1980s around the table with Pierre Trudeau and Jean Chretien regarding the Canadian Constitution.

“He took a tremendous negotiating role in those talks,” recalled Chief Patrick Madahbee, of the Anishinabek Nation Grand Council. “He took a hard line and he always knew his stuff. He was the quickest man to counter any argument.”

Billy’s efforts resulted in Section 35 of the Constitution being amended so that “treaty rights” would include current rights that existed by way of land claims agreements or those that may be acquired. There was now no question that the country’s Constitution protected the claims of his own Crees and all other Aboriginal Canadians.

Though Billy was such a prominent leader “he stayed down-to-earth and was likeable,” said Madahbee. “He kept us laughing through all the political strife. He was an excellent impersonator and he was quite the comedian with his impressions of some of the government politicians we were dealing with.”

In 1982, a coup in Billy’s career came when he sought an audience with Pope John Paul II. Seeking favor with his Cree people who had become suspicious of his high-profile dealings, Billy knew the Catholic church held power over them. He announced the meeting before even fathoming how he would arrange it, but managed to cut through levels of command to find himself at the Vatican telling the Pope about the neglect his people experienced in their own country.

As his public life flourished, the chief’s personal life deteriorated. At 34, he had four children but he was seldom home to see them. Away from his community, he smoked and drank hard with business associates and peers, and he was becoming alienated from his wife.

She had joined the local Pentecostal church and was “reborn.” Billy tore up the simple religious messages Elizabeth left pasted on the refrigerator door and even showed up drunk to an evening service she was attending.

Billy’s residential school days had left him hating God, and he was sure nothing good could come of his wife’s obsession with this judgmental and punishing icon.

After binge drinking and terrorizing his family, he was alone and sick. Overweight and overworked, he was seeing double and his heart raced periodically.

In Val d’Or one night, as he drove himself to the hospital, he turned into the local Pentecostal church. There, he fell to his knees and prayed for himself. A warmth came over him and he stayed “basking in the glow of what was happening to me,” for a long time, he recalled.

The pain in his chest, arms and hands was gone.

Renewed, Billy became a spiritual man, reuniting with his wife and family and quitting booze and cigarettes. In 1984 he informed the Grand Council of the Crees of Quebec that he was stepping down as grand chief.

“I feel the age of confrontation is now basically over and now it’s down to nation building,” he told delegates.

Retiring to his home community, Billy created and fostered ground breaking businesses like Air Creebec and even brokered a deal with Yamaha Motor Canada to re-design old-style river boats and manufacture stream-lined, fibreglass, Waskaganish-built craft.

He would even become chief of his community once again before his passing.

The much-lauded business and political leader, and father of six, died on the morning of Sept. 30 from a heart attack, his wife Elizabeth at his side.