Image Caption

By Shari Narine

Sweetgrass Contributing Editor

EDMONTON

September 12, 2016.

Athabasca University begins a graduate literature seminar this week that speaks to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s calls to action.

“I’ve always included Indigenous literature in all my Canadian literature courses,” said Dr. Di Brandt. “But what is new is … to put (Indigenous literature) in the actual course description as one of the purposes of the course.”

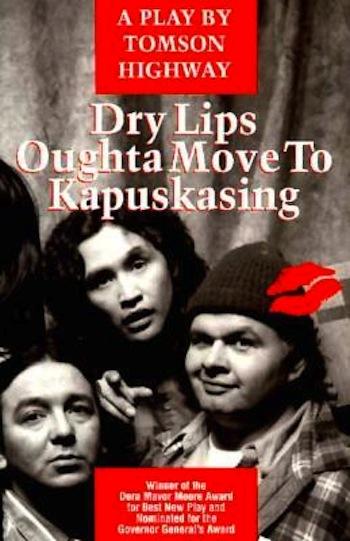

“Poetry and Drama of the Canadian Prairies and the North,” which is offered as part of Athabasca University’s Master of Arts-Integrated Studies, is described as: “an extraordinary collection of exciting, challenging, inspiring, beautiful, diverse works by Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal writers. The course will feature 10 exemplary texts which will develop critical reading strategies that reflect both Indigenous and intercultural engagements in the work of these talented and visionary writers. Furthermore, it will address a range of subjects, including gender, sexuality, colonization, the land, relevant historical events and intertexts, work, humour, love, spirituality, healing, and hope. Students will have a chance to develop both creative and critical responses to these works.”

The decision to emphasize the inclusion of Indigenous literature “is particularly because of the dialogue that is happening now in light of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s process and the encouragement to all the universities to offer Indigenous courses as sort of a core requirement for all people,” said Brandt.

While this is the first year Brandt will be teaching the course for AU, she has been teaching Canadian literature for 30 years, including the past 11 years with Brandon University.

Brandt says Canadian literature got a boost in the early 1970s when the federal government introduced a multiculturalism policy, which in 1988 was adopted as the Canadian Multiculturalism Act.

“After the act, there was a huge explosion of multicultural literature and Indigenous literature in Canadian publishing and studied in Canadian universities,” said Brandt. Up to that point, she says writers had to be either English or French or had to hide their ethnicity in order to be published.

“I feel that one of the purposes of literature is to enable us to understand differences and to celebrate differences and at the same time to find commonalities and to understand each other, so I want to do both of these things. I want to honour different literatures with their different interests and cultural issues and expressions and at the same time, mix them up together so they’re talking together,” said Brandt.

Brandt notes that the traditional method of teaching Canadian literature at universities is to categorize writers according to their genealogies. She says that approach becomes unwieldly with too many ethnic categories.

“I’m not so much (about) putting each text specifically in dialogue with each other text, but rather trying to propose this sort of duo genealogy for our literature. There’s an Indigenous genealogy and there’s an immigrant genealogy,” she said.

Brandt adds that Indigenous literature has been affected by immigrant literature and culture and vice versa and that isn’t always acknowledged.

“That’s what I’m trying to honour and celebrate and highlight and interrogate,” she said.

Brandt isn’t Indigenous but she doesn’t believe that to be an issue. In fact, she says the feedback she has received has been positive, reaffirming her decision to “honour” Indigenous literature in Canadian literature.

On a personal level, Brandt says Indigenous literature – and Indigenous writers – have helped her. Brandt, who is also a writer and literary critic, was raised in a traditional Mennonite community. She struggled to make the “cultural leap” in her writing from traditional to contemporary.

“I was learning how to do that at the same time there was this blossoming of Aboriginal modern writing in Canada. That body of work and those people who were doing that work were so eloquent in being able to describe what that involved to make a very big leap from one kind of traditional culture with traditional values to contemporary and so that is also part of what I’m bringing to this course, a sort of a very deep hands-on understanding of what it means to live in more than one cultural identity in one time and how to make them speak to each other,” said Brandt.

To date, there are six people enrolled in Brandt’s AU course. More can be accepted.

“At this time I think it’s really wonderful there’s this push for greater literacy in the history and culture of our country and of our land and I think it would be fantastic if everybody took courses like that,” said Brandt.