Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

A report more than 10 years in the making on food security and food sovereignty for First Nations across Canada reveals some disturbing findings: almost half of First Nations families have difficulty putting enough food on the table, and families with children are affected to a greater degree.

And the coronavirus pandemic over the last 18 or so months has added to the concerns.

“Generally within Canada there is recognition that COVID-19 has contributed significantly to food insecurity … and definitely exacerbated the issues in First Nations communities,” said Victor Odele, a senior research and policy analyst for environmental health for the Assembly of First Nations (AFN).

Ice roads had shortened lifespans this past year because of the effects of climate change. The cost of food skyrocketed. Access to help from larger organizations who supplement food supplies decreased. And the isolation efforts to protect against the spread of COVID-19 made it almost impossible for people to travel south to supplement their grocery shopping.

The AFN collaborated with the University of Ottawa and Université de Montréal to produce the First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environmental Study (FNFNES), which was released last week.

Eight regions of the AFN comprising 92 First Nations and 11 ecozones participated in the study. Sixty per cent of those First Nations were located more than 50 km from a service centre and 18 per cent had no year-round road access.

The findings are troubling, said Odele.

“First Nations children go to school hungry and many First Nations children go to bed hungry. There is a lot of significance to that, not only in terms of health implications but also in terms of implications culturally, spiritually and socio-economically,” he said.

“I also worry that a lot of First Nations children have been denied access to an important aspect of their components of their culture.”

The report found that while traditional food systems “remain foundational” to First Nations and primarily safe for consumption, access to traditional food does not meet current needs.

Most households “actively engaged” in traditional food use, says the report, with those living in British Columbia most successful and those living in Ontario, Alberta, Manitoba and the Atlantic being “significantly lower.”

This particular loss is complex, says Odele, “recognizing that for First Nations, food is not just about nutrition, but more importantly about culture, about the sacredness of food… and also the recognition that traditional food cannot be substituted or replaced by store-bought food.”

The report found that “structural level barriers” to harvesting existed where industrial activities and climate change impacted availability; government regulations caused issues; and households lacked a hunter, sufficient resources to purchase or operate equipment, and time.

The lack of traditional food activity also tied into lower rates of self-reported good health.

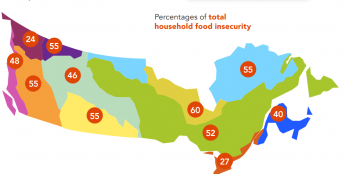

FNFNES also examined the financial ability of households on-reserve to purchase food from stores and found the lack of economic access to store bought food ranged from 48 per cent to 60 per cent, with the highest in Alberta and remote communities.

The study also found that the diet of First Nations adults does not meet nutritional recommendations and, in limited cases, there are health concerns. The mercury levels in large predatory fish, particularly in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec, could be of concern to women of childbearing age; and the use of lead-based ammunition for hunting resulted in “very high levels” of lead in harvested mammals and birds.

Among the six recommendations included in the study is the creation of a joint task force to operationalize the other five recommendations:

- support initiatives that promote Indigenous rights, sovereignty, self-determination, values and culture;

- prioritize the protection of First Nations lands and water;

- build capacity to reduce food insecurity;

- improve collaboration between all levels of government;

- and support continuing research, education and public awareness.

“The task force is not to provide a national solution… but bring the discussion to the national level. It’s to create something to start the implementation of some of the findings so this doesn’t end up as one of those reports that just sits on the table and without any operationalization,” said Odele.

The task force will ensure that First Nations rights holders are involved in Canada’s national food policy and raise First Nations priorities and context when it comes to addressing food security and food sovereignty, he adds.

Odele says there is recognition that the recommendations “require some financial aspect,” but he is uncertain whether the task force will put forward a dollar figure.

The study was designed to report results region by region, starting in British Columbia in 2008 and concluding in Quebec in 2019. Each region required a three-year cycle to complete community engagement, data collection, and data analysis. Both community-specific and regional reports were provided.

The draft final report was published in 2019, with feedback collected from participants.

“There is a lot of work going on at the community level and regional level around food sovereignty and food security. This study has contributed in terms of providing guidance, providing additional tools for communities and regions to use to continue to advocate for food security and food sovereignty,” said Odele.

Moving forward, he says the study provides baseline data that can be used to compare future research and findings from each region.

It also serves as a springboard for other research, such as the Food, Environment, Health and Nutrition of First Nations Children and Youth (FEHNCY) study now being led by the AFN, University of Ottawa and Université de Montréal.

To see more on the key findings of the report check out: http://www.fnfnes.ca/docs/CRA/FNFNES_Final_Key_Findings_and_Recommendations_20_Oct_2021.pdf