(Editor’s note: It was around this time in the year 2000 that Windspeaker staff were preparing for a new section in our print news publication. Buffalo Spirit, a 12-page supplement folded into our monthly news magazine, would become a quarterly feature. And it all began with a mission by publisher Bert Crowfoot to reclaim something important he felt was missing from his life. This publisher’s statement explains how Windspeaker became committed to sharing Buffalo Spirit ideas, philosophies, and teachings.)

By Bert Crowfoot, publisher and CEO of the Aboriginal Multi-Media Society of Alberta (AMMSA)

Excerpted from his statement on publishing the first Buffalo Spirit pages in February 2000.

Buffalo Spirit began with a journey; a journey of self-discovery about Indigenous cultural and spiritual roots.

Buffalo Spirit is for those individuals who are searching for who they are and where they come from. There is a lot of confusion when it comes to these matters. It is especially confusing for those individuals who grew up in the city and not on the reserve. I am one of those individuals.

My parents wanted a better life for me and sent me to the city to live with a non-Indigenous family when I was 12 years old. The only time I came home was in the summer and I spent most of that time working for my father or local farmers. I was never abused and was treated well by my non-Indian families, but as a result I lost my culture.

My father was Siksika (Blackfoot) and my mother was Saulteaux. English was the only language that was spoken when I was growing up.

As an adult, I used to dance at powwow and was a craftsman, making Navajo jewelry and other handicrafts. I was doing cultural things, but I didn’t feel it inside. Something was missing and I didn’t know what it was.

Mainstream religion was not the answer I was searching for. What I was searching for was Indigenous spirituality. I had so many questions and wasn’t too sure where to go for answers. Here I was, a Blackfoot/Saulteaux, married to a Navajo, living in Cree territory. I was really confused. And as I looked around, I saw many others who were also confused and were on the same journey that I was on.

I asked many questions and turned to my advisors, Joe Cardinal and Devalon Small Legs. I asked them to meet with AMMSA staff and provide us with a cultural workshop. We had many questions for them and provided the questions to them the night before the workshop. We quickly discovered that the move forward was not a question-and-answer session. The answers we received came in the many stories that they told.

We were also told that the most important thing was to be PATIENT and accept those things we don’t yet understand. Both advisors stated that they were not Elders and did not consider themselves worthy of the title of Elder. They were not perfect and were only human beings. However, they provided many answers that day.

Another area I searched was the Internet. I looked to modern technology to see what was out there. The one thing I noticed was that the descriptions of the Sundance by non-Indigenous observers was very different than in the writings of Indigenous writers.

Non-Indigenous descriptions included words like pagan rituals, heathen, savage, torture, etc. To understand the Indigenous perspective, Indigenous people must be given the opportunity to tell their own stories.

Another thing adding to the confusion is how ceremonies have changed. I heard about a ceremony that somehow was changed over the years and is now done backwards. In the past, spiritual leaders were quick to correct these mistakes and ensure the purity of the ceremonies.

We have lost many of these spiritual leaders and with their passing goes that knowledge. What can be done to preserve this knowledge?

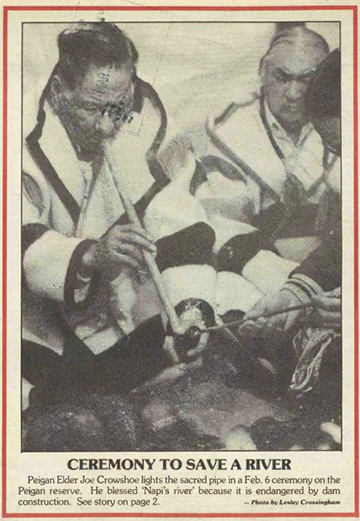

The late Joe Crowshoe, a spiritual leader from the Peigans, once allowed a pipe ceremony to be photographed because he felt that it was important the ceremony be preserved. Is this the answer?

In speaking to author Ed McGaa, he told of a documentary on an Indigenous people in South America. These people were very isolated and did not have contact with mainstream society. Their ceremonies were pure. A television crew came out and recorded their ceremonies. When they saw these ceremonies on television, they said it was good. The ceremonies could be seen by future generations.

Buffalo Spirit was originally going to serve a geographical location and we had three different areas to choose from. As I journeyed to these different markets, it became clear that this was not the direction Buffalo Spirit was supposed to go.

When in Rapid City, South Dakota, I happened to pick up McGaa’s book called Mother Earth Spirituality. McGaa’s writings fascinated me and I bought all four of his books. His words seemed to answer a lot of my questions.

I went to my first sweat this past fall and prayed to the Creator, to the Grandmothers and Grandfathers for answers to the many questions I had. I spent time soul searching in the mountains around southern Alberta about whether it was right to publish stories on cultural and spiritual matters. The answer I received was that the time was right, and that Buffalo Spirit had a purpose.

You may not agree with it, but what is important is that Buffalo Spirit allows us an avenue to discuss these matters and allows us to share with others the beauty of what being Indigenous is all about. The more discussion we have, the more we will learn by sharing. We invite you to share your ideas with us, your experiences, your philosophies.

You will notice as you read Buffalo Spirit that some Elders and knowledge keepers hold very different views on how things are, and how ceremonies should be conducted. For example, some Elders believe men and women can do sweatlodge ceremonies together. Some others say that is, absolutely, not allowed. Both perspectives are correct, according to different customs.

I’m happy that Windspeaker is taking a role in assisting people who are looking to begin their journeys or who are on the journey already.

Being Indigenous is about sharing; sharing not only to feed our physical beings but to feed our spiritual beings as well.

May the Creator be part of your life and may your journey be a good one.

Top Photo: Bert Crowfoot received an honorary doctor of laws degree June 8, 2023 from the University of Alberta for his life’s work in Indigenous communications and for preserving the spiritual practices of different nations in a way that is respectful and honours the protocols, sanctity and supernatural forces that are present in Indigenous spiritual rituals, nature and life. Later that month, on June 30, his family transferred the headdress he is wearing in this photo during a ceremony held at the Siksika Nation in southern Alberta. Photographer is Dave Brosha.

Support Independent Journalism! SUPPORT US!