Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

For Kevin Settee, Cree-Anishinaabe filmmaker, community building is the biggest part of making a film.

He has spent the past two years filming in the Anishinaabe, Cree and Métis communities around Lake Winnipeg. The result is four intimate snapshots of life in four communities: Matheson Island, Poplar River First Nation, Fisher River Cree Nation and Camp Morningstar. The docuseries is called “The Lake Winnipeg Project”.

The four short films cover a range of themes, from the beauty of the UNESCO World Heritage site Pimachiowin Aki, “the land that gives life”, to the power of collective action in Morningstar, a sacred camp established in response to a proposed silica sand mine project.

Through filmmaking, Settee shows the beauty of his culture and highlights the importance of an “own voices” approach.

“I didn't impose any ideas of what I wanted to do. We worked collaboratively, right from the beginning to the end.” Settee said.

The series of documentary short films will be released on June 21. It is his first time writing and directing with the National Film Board.

“Doing community-based research means working with people before we started filming, coming up with the ideas with the communities,” he said.

Settee has family roots in Fisher River Cree Nation, Matheson Island and Dauphin River.

He believes in the importance of listening to what communities and individuals want to share versus going in with a predetermined story idea.

“We started off with community-based research, visits and meetings. We didn't bring our cameras. We just drove around the lake, talking to people and sharing what's happening, the challenges and the good things,” he said.

Challenges include the impacts of shifting climate, industrial encroachment and government policy. The good things relate to being on the land, culture, connection and sharing.

Settee comes from a community organizing background, so he brought those skills and knowledge into his filmmaking process.

“We had community meetings. We literally would pack a hall and ask people ‘What can you tell us?’”

In addition to community meetings, Settee spent time fishing, hiking and out on the water with community members. This was how he learned about the communities in a deeper way.

He said 95 per cent of the filmmaking was the work before the filming, the community connections made.

“Then the filming is just the cherry on top kind of thing. It has to be done properly,” said Settee.

Settee will share more of his process after the premiere of the docuseries on June 21 through the National Film Board. Register here for the post-screening panel discussion with Settee and community members Kailey Arthurson (Fisher River), Marcel Hardisty (Camp Morningstar), Ivy Canard (Sagkeeng), and Waylon Bittern (Poplar River).

In the beginning, the project was to be co-directed. The National Film Board had an idea with a director. A producer approached Settee to come on board as a writer and co-director.

When the other director stepped out of the project for personal reasons, Settee knew it was right for him to direct this series on his own because of his roots all around Lake Winnipeg.

“I told the NFB that I can do this on my own. I can write this on my own. I can direct this on my own.”

Settee took on the directing, working from his deep connections to the people involved.

Settee sees a need for the NFB to have “more Indigenous people, people of color, Black people and women working in the organization.”

For his project, Settee felt like he was given the lead to create his own process of working in community.

“Working with, literally, my family and my friends and my communities, where I come from. To have the resources and the money that they spent to make these things happen. It's how it should be done,” said Settee.

“The momentum is just going to keep going. I encourage artists to get involved making and writing, directing, sound. We need to be the ones telling our stories.”

As a youth, Settee had an awareness of the bias communicated by the media.

He remembers clearly the feeling of being a young Indigenous man watching the news after school in Winnipeg. There would be 20 minutes of regular news, and then right at the end, something like ‘Crime Stoppers’, he said.

He remembers asking his mom, “Why do they have to do that? Why do they have to show that? And they were all Native guys that looked like me.”

This awareness led him to wanting to educate himself on what was happening internationally. He is a co-founder of Red Rising Magazine, and is now focusing on documentaries.

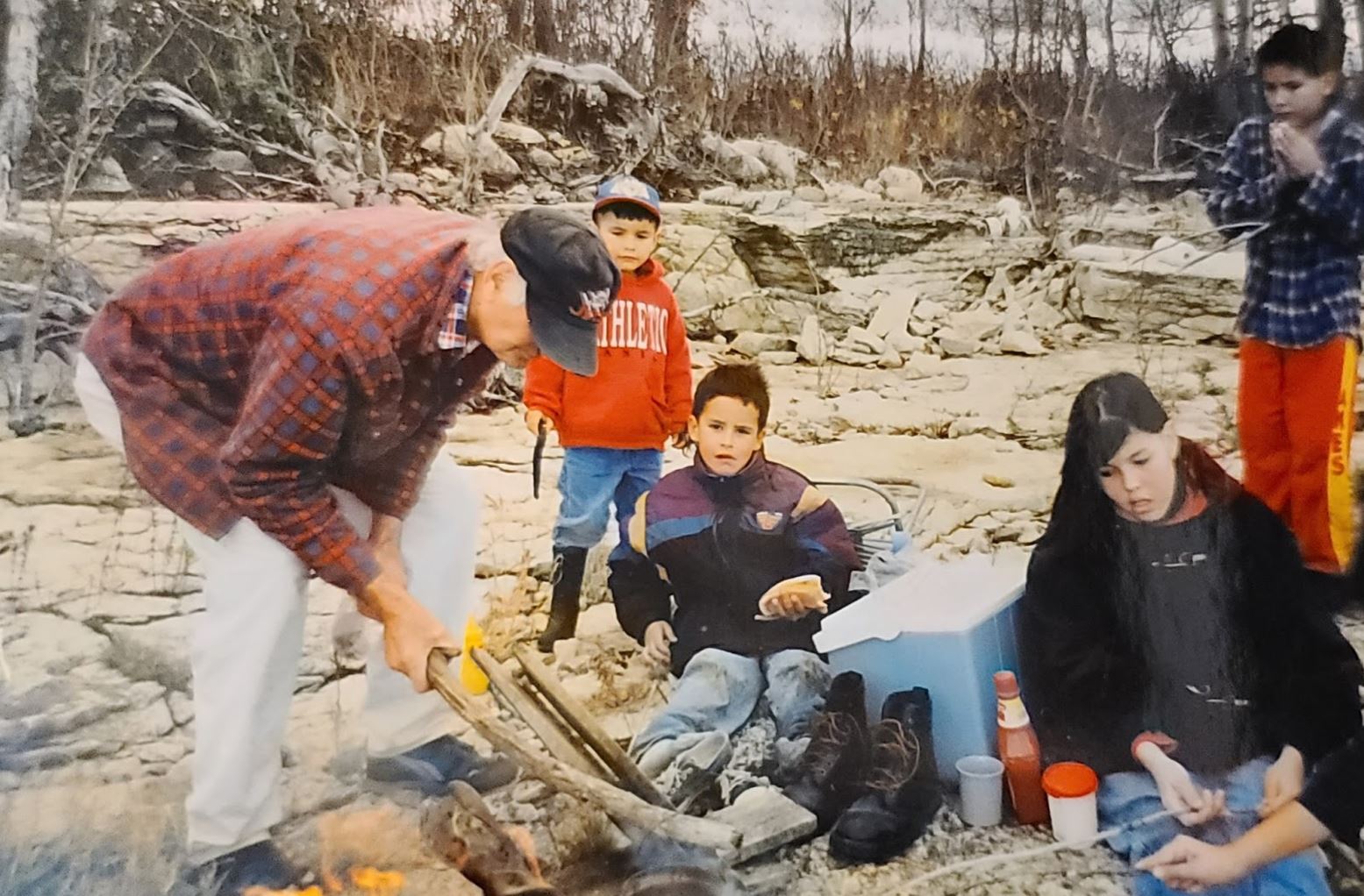

Settee’s childhood had a photographer mentor built in, his grandmother Dorothy Gladys Settee of Fisher River First Nation.

Settee has an appreciation of the responsibility to his people to tell stories in a good way.

“People need to be connected to these places. There needs to be a purpose there.”

“You can't just have anybody coming in and telling our stories. It's very serious, our stories and our history. They're very sacred. And it's something that shouldn't be taken lightly at all.”

Knowing what to share, and what not to share was a significant part of that responsibility.

“In the editing process, what do we want to show? What do we not want to show? What is the most respectful way to show this?”

Sacred sites and teachings were clearly not for public sharing and Settee took care when choosing what to show of a sweatlodge.

“In Camp Morningstar, it’s very intimate. We show the sweatlodge, we show the rocks, we show people getting into the sweat.”

There was a compelling reason behind that choice.

“I come from a place where there's a lot of terror, a lot of hurt. There's a lot of pain.”

“I want people to see our culture. I want people to see our sweatlodges. I want people to know what these things mean, because they were taken away from us. They were stolen from us; beaten out of us.”

Settee thinks of places and people he knows.

“I hope they see these films. I hope it inspires them. I want to show their beauty. I want people to see that. I don't want our people to be scared to share who we truly are.”

“It's important to me, and will continue to be important to me moving forward.”

Local Journalism Initiative Reporters are supported by a financial contribution made by the Government of Canada.