Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

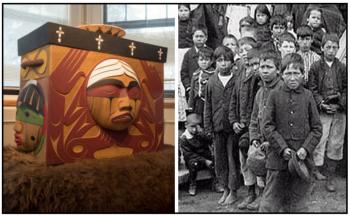

The finding of the remains of 215 children in an unmarked mass grave on the grounds of the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia, announced last week by the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation leadership, provides a stark reminder.

Six years after the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) on Indian residential schools leveled 94 Calls to Action, few of them have been completed.

The Pope has yet to apologize for the Indian residential schools operated by the Catholic Church. The Kamloops school, once the largest residential school with about 500 students at its peak, was operated by the Catholic Church from 1893 to 1969. The federal government took it over and ran it as a day school for almost a decade before it was closed in 1977. Call to Action 58 calls for the Pope to apologize and despite a personal request by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in 2018, the apology has yet to be delivered. Other churches have apologized for operating Indian residential schools in Canada.

June marks six years since the TRC delivered their Calls to Action on the legacy of the Indian residential school system. Six months later, in December 2015, the commissioners delivered their final report, encompassing six volumes, and called what happened in the schools “cultural genocide.”

Calls to Action 71 through 76 deal with the children who went missing during their attendance in residential schools. Falling under the subtitle of “Children and Burial Information,” it calls, in part, for “records on the deaths of Aboriginal children in the care of residential school authorities to make these documents available to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation.”

Based on death records, the NCTR estimated about 4,100 children died at the schools, but believes that number to be low. The deaths of those children who were found buried on the grounds of the Kamloops residential school are undocumented.

Calls to Action were directed at various levels of government, churches, educational institutions, legal system, museums and archives, media, sports operators, and business.

On its website, the federal department of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs has outlined the work it has undertaken on the Calls to Action that require Ottawa’s lead. However, that site has not been updated since September 2019.

There are a handful of independent organizations tracking the progress on the Calls to Action.

Douglas Sinclair of Peguis First Nation started his website, Indigenous Watchdog, in April 2016 after retiring from his work in the technology industry.

“I thought it would be interesting to track and see what’s going on. There really wasn’t a lot of visibility at that time. There still isn’t a lot of visibility,” said Sinclair, who is first cousin to TRC Chief Commissioner Murray Sinclair.

Also tracking the Calls to Action are the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), the Yellowhead Institute, and Beyond 94 by CBC News.

Every tracker has a different method of tracking the calls and assigns varying status values.

The number of Calls to Action completed since 2015 range from Indigenous Watchdog’s low of six to Beyond 94’s high of 10.

The Yellowhead Institute’s latest accounting, which was done in 2020, claims no new Calls to Action were completed that year. The institute states it no longer marks calls as “in progress” as that designation in many cases has not led to completion.

“That they are not (completed) speaks to the limits of measuring progress by promises and exploratory committees struck rather than by real, meaningful action,” write authors Ian Mosby and Eva Jewell.

The Yellowhead Institute has marked eight calls completed since 2015.

Douglas Sinclair contends his number of completed calls is possibly lowest because “one of the key things I do that nobody else does is differentiate between First Nation, Métis and Inuit because they each have distinct needs.”

For example, he says, while the AFN and the Métis National Council may consider Call 14, which pertains to the Indigenous Languages Act, as complete, Sinclair does not. He points out that the federal government ignored the push by numerous Inuit organizations to have Inuktut given official language status within the Inuit homeland of Nunangat.

Sinclair last updated the status of the Calls to Action on March 31, 2021. He uses a variety of sources ranging from the Aboriginal Law Report to websites of businesses, organizations, associations and universities.

“Some of the information is problematic because it’s not readily available,” he said, admitting it’s a “full time job” to do the research necessary to keep the progress on the Calls of Action up to date.

Sinclair believes that many of the changes called for will be generational in coming, but he admits the progress to date “is not very good at all.”

He’s not alone in that assessment.

Last December in marking the five-year anniversary of the TRC’s final report, Chief Commissioner Sinclair was joined by his fellow commissioners Chief Wilton Littlechild and Dr. Marie Sinclair in expressing their disappointment.

“This reconciliation and healing are matters of urgency,” said Murray Sinclair. “Overall, the federal government has been slow in implementing the TRC’s 94 Calls to Action.”

At that time Littlechild talked about his disappointment that the United Nation’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) had yet to be implemented as law by the federal government. For Wilson, it was the lack of the creation of the National Council for Reconciliation (NCR). They referred to these actions as the “two pillars.”

“Five years later we did expect to see real progress in laying the foundations for national reconciliation and specifically the two missing pillars needed to support all the rest,” said Wilson.

Just last week, Bill C-15, which is legislation meant to harmonize Canada’s laws with UNDRIP, received third and final reading in the House of Commons and was passed on to the Senate. Bill C-15, however, was not endorsed by chiefs at last December’s annual general assembly for the AFN, despite an impassioned plea by Littlechild to do so. Littlechild admitted the bill had “room for improvement,” a view held by many chiefs, who decided not to go ahead with a resolution supporting the bill because the AFN had not allotted enough time during the meeting for the full discussion that was required. Calls for every level of government to adopt and implement UNDRIP and for the federal government to develop a national action plan are recognized in Calls to Action 43 and 44.

As for the establishment of the NCR through federal legislation, which is Call to Action 54, the federal government announced $126.5 million in budget 2019 for fiscal years 2020 and 2021 to establish the council. Beyond 94, which was last updated on April 12, 2021, has that call as “not started.”

“Today we are concerned by the slow and uneven pace of implementation of the Calls to Action,” said Littlechild back in December, adding that the “sense of urgency, purpose, and unity” that the TRC’s Calls to Action were received with in 2015 no longer seem to be there.

According to Yellowhead Institute, at the rate the Calls to Action are being completed “we could only hope to see substantial change over nearly four decades.”

Douglas Sinclair says Indigenous peoples need to use all the tools in their toolbox—including court action and strong leadership—to force the changes called for by the TRC.

“The broader you make your tool kit the more leverage you can position against whoever is standing in the way of progression,” he said. “You have to have as many tools in your hand available to be able to adapt to any situation that comes up. The strongest, unified approach you have (is) the most likely grounds for success.”

(Reading articles about residential schools, particularly about the discovery of the 215 children's bodies discovered in Kamloops, may trigger strong emotions. If you are having difficulties in dealing with these thoughts and feelings and are in need of support, call the Indian Residential School Survivors Society emergency crisis line at 1-866-925-4419. Help is available 24/7.)