Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

A picture is worth a thousand words. That’s the cliché that’s been utilized for generations.

But in a webinar hosted Wednesday, Aug. 19 it was suggested that people use a critical eye to determine what they are really seeing in images of sports from Indian residential schools.

That’s because what people believe they’re looking at might not be the true story.

The hour-long webinar featured Janice Forsyth and Alexandra Giancarlo. Forsyth is a leading Indigenous sports historian and an associate sociology professor at Western University in London, Ont. She’s also the director of Indigenous Studies at Western. Giancarlo is a postdoctoral associate working with Forsyth through Western’s Indigenous Studies program.

It was hosted by Algoma University, located in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., as well as the Algoma University Archives. The event was part of the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre webinar series. Shingwauk is an education centre and archival repository within Algoma University, which was partly built on the former residential school grounds.

Forsyth spoke on a segment titled Don’t Let Pictures Fool You, a theme that continued throughout the presentations.

Forsyth said sports photos taken at residential schools had a specific intent.

“It was always to show the school in a good light,” she said. “You don’t see abuse or loss in the photos.”

It’s important to consider what the audience is meant to see, or perhaps not see, from certain photos, Forsyth said.

She said it’s vital to try to understand who is in the picture and if possible their reactions to being photographed.

Those looking to better understand photos should try to find documents to help explain the photos’ contents of a photo.

“Can I access survivor testaments about their time playing sports at schools,” said Forsyth.

During her presentation, Forsyth talked about a segment dubbed Theoretical Toolkit To Guide Our Understanding.

In this portion, Forsyth mentioned how sports images could create a “false equivalency”. Individuals seeing the photos could form their own conclusions about Indigenous residential schooling and life simply by superimposing their own educational experiences onto the images.

“The photos act as body of knowledge about the school and what the students’ experiences were there,” she said.

Forsyth discussed the positive assumptions photos were intended to evoke, which were, in part, to suggest life and sports at residential schools were all about fun, friendships, freedom and health.

“Sports photos also played a strategic role in shaping public views of residential schools and the system,” Forsyth said.

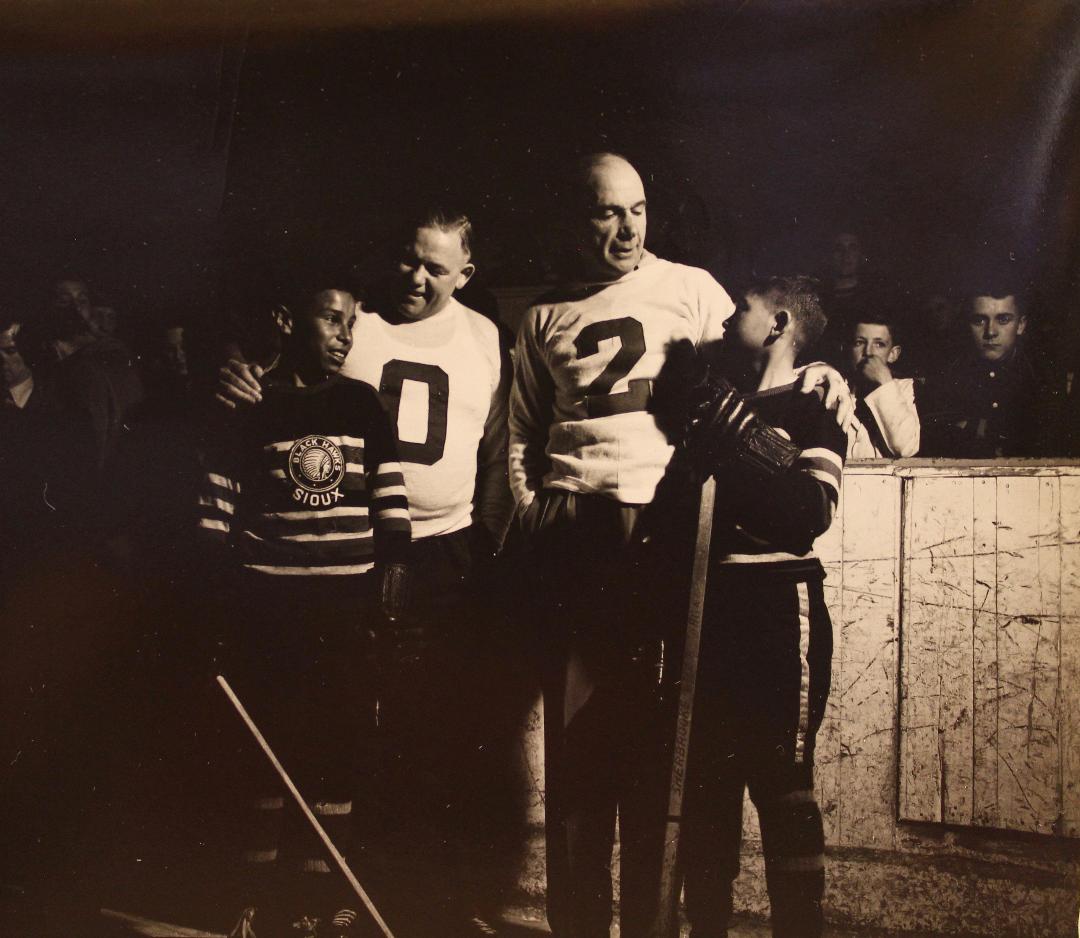

Giancarlo focused her presentation on her postdoctoral research work titled “Crossing The Red Line: The Story of the Sioux Lookout Black Hawks.”

This research examines a Midget boys’ hockey team from a northern Ontario residential school that toured southern Ontario in 1951, playing various exhibition contests and visiting famous landmarks, including the Parliament buildings.

“In the pictures the boys look to be relatively happy and well taken care of by their coaches,” she said. “We know the realities were a lot more stark.”

The tour was organized by the department of Indian Affairs, but the same year the Black Hawks toured southern Ontario the school was being criticized for its deplorable state.

“In fact, they were told if they did not improve the conditions and make repairs the school would be closed immediately,” Giancarlo said, paraphrasing a school official who conducted an inspection.

“It was to show the success of the school and the so-called good work the schools were doing,” Giancarlo said.

Giancarlo is intrigued by the research on the Black Hawks, which included testimonials from three surviving members of the team.

“I’ve always been interested in elevating the history of disenfranchised groups in North America,” she said.

Like Forsyth, Giancarlo believes it’s important to resist forming judgements simply by looking at sports photos from residential schools.

“You can’t take them at face value,” she said. “They would have been trying to promote a certain positive image.”

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada shed light on the dismal, harmful conditions at Indian residential schools in Canada, despite what the sports photos attempt to communicate.

“We know from survivors’ testimony the schools were rife with physical and sexual abuse and humiliation of the students," said Giancarlo.