Image Caption

Summary

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

Correction: Brittany Luby said the Canadian government previously denied her claim, stating her grandmother had voluntarily enfranchised with her father. But Lucy said they were involuntarily enfranchised.

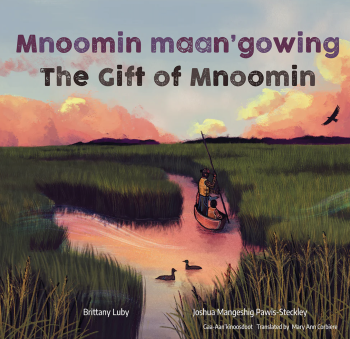

The circle of life is explained in an upcoming children’s book written by Indigenous author Brittany Luby.

The book, which is published by Groundwood Books and will be available on Oct. 3, is titled Mnoomin maan’gowing The Gift of Mnoomin.

The 36-page book, aimed at children ages three to six, is written in both English and Anishinaabemowin.

It tells the story of a young child who is holding a single mnoomin seed and imaging all the living creatures that made that seed possible.

Mayfly, Pike, Muskrat, Eagle and Moose all had roles to play.

The book follows the child and family during a harvest day as they make offerings of tobacco and then collect seeds in their canoe.

Once they’re back on land, family members prepare the seeds and cook a feast. Some seeds are roasted and dried for winter consumption. And some seeds are put aside to be returned to the field.

“An ecosystem is a community of interconnected organisms and their environment,” Luby wrote in an ecological note at the back of her book. “Mnoomin provides shelter to young creatures like fish fry and ducklings, which, in turn, feed other creatures like herons and humans.”

Luby also said mnoomin has varying translations. Some Anishinabeg translate the word to spirit berry since ‘mnidoo’ means spirit and ‘min’ is found in other words for berries, including mskomin (strawberry) and mshkiigmin (cranberry).

One thing Anishinabeg agree on is that mnoomin is not wild rice.

“This culturally significant food is not ‘wild’,” Luby said. “To ensure the survival of mnoomin for future generations of human and other-than-human beings, Anishinabeg sow a portion of the seed they harvest each year.”

Luby is hoping there is a simple takeaway from those who read Mnoomin maan’gowing The Gift of Mnoomin.

“I hope this book reminds readers that we are deeply interconnected with all creation, from Mayfly who feeds Pike who, in turn, fertilizes Manoomin who, in turn, feeds us,” she said. “When we harvest and reseed the fields, we return the gift of life to others.”

Though it was written for young children, Luby said her book has a message for all, regardless of how old they are.

“Whatever our age, whatever our growing up experiences, Manoomin shows us that the ancestors prepared for our arrival, harvesting and reseeding fields in anticipation of our births,” she said. “Manoomin is a symbol that we, the children of Anishinaabe-Aki, were loved long before we were born.”

Luby also explained the importance of having the book written in two languages. She said her great-grandfather was a residential school survivor.

“When he became a father, he chose to raise his children in English in hopes of protecting them from harm,” she said. “His decision has rippled across the generations as I too was raised in English. Although I do not speak Anishinaabemowin at this time, I feel it is important for the next generation to see, if not hear, the language in our family home.”

Luby said collaborating with language speakers “is an act of hope. Hope that I will one day be able to read it to my children. Hope that my family will reclaim the voice we lost with the support of the friends we've found.”

Luby is non-status whose father is a former chief and member of Niisaachewan Anishinaabe Nation in northern Ontario. She is hoping an amendment to the Indian Act will allow her to claim her First Nations status.

Luby said the Canadian government previously denied her claim, stating her grandmother had voluntarily enfranchised with her father. But Lucy said they were involuntarily enfranchised.

She wrote her initial draft of her book early on during the pandemic.

“I consider the fields a safe place,” she said. “I feel loved and protected by my ancestors, and other-than-human relations with whom I share these spaces. I imagined myself on the river to help ease the anxiety of COVID-19, to return to a place I could not travel to. The Gift of Mnoomin began as an act of self-care.”

Luby said an Elder notified her of the importance of sharing her teachings with others.

“He felt it was essential that I communicate the connectedness of all living beings through my work,” she said. “This inspired me to share The Gift of Mnoomin with others. Perhaps they needed this story too.”

The book is illustrated by Joshua Mangeshig Pawis-Steckley, a member of Wasauksing First Nation in Ontario.

The book will be available for purchase on Oct. 3 through this link: https://houseofanansi.com/products/mnoomin-maangowing-the-gift-of-mnoomin?_pos=1&_sid=ab648c54f&_ss=r