By Cheryl Petten

Windspeaker.com Archives

Norval Morrisseau has been known by many names. Some have called him the father or grandfather of Native Canadian art. Others dubbed him the Picasso of the North. He was also known as Miskwaabik Animiiki, or Copper Thunderbird, the name he was given when he was 19 and gravely ill and which he credited with saving his life.

Morrisseau was born on March 14, 1932 in Fort William, now part of Thunder Bay, Ont. He was the eldest boy in the family and, as such, was raised by his grandparents according to Anishnaabe tradition.

He grew up on Sandy Point reserve, where his grandmother introduced him to Catholicism, while his grandfather shared with him the stories he’d learned from his grandfather before him—stories of Anishnaabe myths and legends.

The teachings of both grandparents had a huge impact on Morrisseau, and would be reflected in the works of art he produced throughout his lifetime.

Morrisseau’s time of learning from his grandparents was cut short when he was sent away to a Catholic boarding school, where he endured abuse—physical, sexual and emotional. After two years he returned home and spent another two years attending a school in the community before his formal education came to an end.

Although he was no longer attending school, Morrisseau was eager to continue his learning, but now his teachers would be his grandfather and the other Elders in the community. The young boy had aspirations of one day becoming a shaman, and as such was eager to gather any and all wisdom they chose to impart.

When he wasn’t spending time with the Elders, Morrisseau liked to draw, putting to use his talents as a natural born artist. Later in life, he would find a way to merge these two identities—shaman and artist—into one.

Morrisseau drew inspiration for his paintings from many sources—from the ancient pictographs he saw painted on rocks near his home community, from Midewiwin scrolls such as the ones he’d watched his grandfather create, and from his grandfather’s stories.

Other inspiration, Morrisseau would tell people, came from the House of Invention, a place he would travel to in his dreams, another realm where all the works he had yet to create would be laid out before him.

When he began to paint images inspired by Anishnaabe ancient stories, many in the Aboriginal community, most notably the Elders, were not pleased that he was creating these paintings and sharing them with the world. Even Morrisseau had doubts as to whether he was crossing a line with the subject matter, but his fears were eased by a dream he had in which the Great Spirit told him to continue his work.

The art he created was so innovative and unique that it spawned an entirely new style of Native art—the Woodland, or Anishnaabe, school of art—which features X-ray-like images of people, animals and spiritual beings, rendered in bright colours, with thick, black lines outlining and connecting each figure.

Morrisseau credited a visit to the House of Invention—and his tours of art galleries in Europe, where he found the works of the great masters to be dark and colourless—with inspiring him to introduce the bright colours so prominent in much of his work.

Over the years, many people have told Morrisseau his paintings have healed them, and he linked those restorative powers to the colours in the paintings and the emotions they invoke.

Although he’d been an artist all of his life, it was in 1959 when Morrisseau decided to make art his career.

His first major success came in 1962, when he had his first showing in Toronto. Five years later, his work was introduced to an international audience when two of his murals were featured at the Indian pavilion at Expo ’67 in Montreal.

In 1973, Morrisseau joined together with six other First Nation artists—Daphne Odjig, Jackson Beardy, Alex Janvier, Eddy Cobiness, Carl Ray and Joe Sanchez—to form Professional National Indian Artists Inc., a group that soon became known as the Indian Group of Seven.

Over the years, Morrisseau accumulated a long list of honours and accomplishments. In 1978, he was appointed a member of the Order of Canada, and in 1986, he was named a Grand Shaman of the Ojibwa people.

In 1989, he was the only Canadian artist invited to show his works as part of an exhibit held at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris to mark the bicentennial of the French Revolution, and in 1995, the Assembly of First Nations honoured Morrisseau by awarding him with an eagle feather.

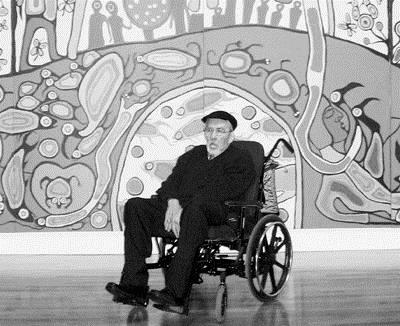

In 2005, he was elected a member of the Royal Society of Canada’s Academy of Arts. And in 2006, Morrisseau became the first First Nation artist to be featured in a solo exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada.

That exhibition, Norval Morrisseau—Shaman Artist, ran at the gallery for three months before travelling to the Thunder Bay Art Gallery, then the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg before heading to the National Museum of the American Indian in New York City, where it wrapped up a four month stay at the beginning of January, 2008.

The latest addition to the list of Morrisseau’s many accomplishments is a 2007 Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Aboriginal Achievement Foundation.

While Morrisseau’s career and life contained numerous high points, they were countered by an equal number of lows, at times when his drinking got the better of him.

For a time in the late 1980s, Morrisseau was living on the street, and selling his paintings. It was then that he met Gabor Vadas, a young man who was also living on the street and who had just lost his father. The two formed a bond, and with help from Vadas, Morrisseau left the alcohol and drugs behind and once again channeled his energy and creativity into his art.

He created a number of pieces during this time, some of which have been called his greatest works. But this creative period was not to last for long. Within a decade, Morrisseau developed Parkinson’s disease, and as his condition worsened, it robbed him of his ability to continue painting. He died of complications of Parkinson’s on Dec. 4, 2007.

Morrisseau’s career as an artist spanned nearly half a century.

“I wanted to be a Shaman and an artist. I wanted to give the world these images because I felt this could bring back the pride of the Ojibwa, which was once great,” Morrisseau says in the book Norval Morrisseau—Return to the House of Invention.

“My aim is to reassemble the pieces of a once-proud culture, and to show the dignity and bravery of my people.”