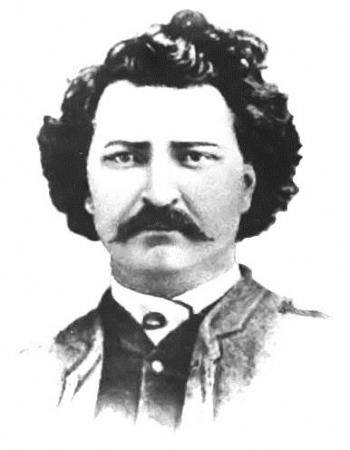

Image Caption

By Dianne Meili

Windspeaker.com Archives

February 20th is Louis Riel Day, commemorating the martyr of the Métis people. Born on Oct. 22, 1844, Riel's role as the undisputed spiritual and political head of the Métis was set by religious parents and authorities who recognized his brilliance at an early age.

His father Louis Riel and mother Julie Lagimodiere were both devout Catholics, and had considered a religious life before marrying each other. Their piety was an important factor in the family's daily life.

Young Louis Riel spent his childhood on the east bank of the Red River, growing up among the Métis and extremely conscious of his identity, inherited through his father's line.

He began school at the age of 10, and was sent to Montreal to study for the priesthood. Immersed in Latin, Greek, French, English, philosophy and the sciences, Riel placed himself at the top of his class until the death of his beloved father in 1864. His grief overwhelmed him; his interest in his studies waned and he eventually left school altogether.

After his romance with a young woman named Marie Julie Guernon was disallowed by her parents, who didn't want their daughter marrying a Métis, Riel then disappeared to the United States. He arrived back in St. Boniface as an unemployed man.

The fact that he was educated,however, as well as ambitious and bilingual, made him a perfect choice to lead the Métis in their fight for rights in the Red River settlement.

He spearheaded the writing of a "List of Rights" in 1869 that preceded the entry of Manitoba into the Confederation. In part, the List of Rights included such provisions as:

- the people will have the right to elect their own legislature;

- English and French languages will be used by the government;

- and all sheriffs, magistrates, constables, and school commissioners will be elected by the people.

A group of transplanted Loyalists saw this list as evidence of sedition and they had the ear of the Government of Canada, which procrastinated in accepting the List of Rights.

When Riel established a Provisional Government to help block the inclusion of the Red River territory in the United States, his efforts were judged as revolutionary. A group of Orangemen from Upper Canada also took their revenge on Riel's Provisional Government by trying to overthrow it.

Thomas Scott, an exceptionally violent and racist man, was caught and charged with treason for his role in the overthrow. After a lengthy trial, Scott was found guilty and killed by firing squad.

Enraged anti-Catholic and anti-French sentiment in Ontario blocked Riel from taking his seat in the House of Commons, and, in retaliation for his part in Scott's death and playing a part in the creation of the Provisional Government, Riel was banished to the United States in 1875 for five years.

Isolated and lonely, Riel brooded in severe depression punctuated by euphoric states of joy. He was lonely, cut off from his people and country, but he began encountering the "divine spirit", which led him to believe he had a religious mission to lead the Métis people of northwest Canada.

While quietly teaching at a Montana Jesuit Mission, Riel received a visit from a delegation of Métis who had traveled from northern Saskatchewan where they, along with other Métis families, had settled after 1869. They told Riel they had resumed their traditional way of life, but they were now threatened again by the influx of settlers and immigrants.

Their borders were again disappearing, their rights were no longer being respected, their lands were being taken and the government was not listening.

Riel helped them petition the government, which promised, a year later, to appoint a commission to investigate the Métis' claims and titles. The first step would be to take a census of the Métis. These proposals angered the Métis who were hoping for a quicker solution to their problems.

Desperation escalated throughout the hungry winter of 1885, when Indian tribes, dying of hunger and disease, joined Riel's cause. Once again, Riel formed a provisional government and decided to capture Fort Carleton without violence, and use it as his base, but the Mounted Police reinforced its garrison.

Riel asked for the peaceable surrender of the fort, but then skirmishes between Indians and police led to increased hostilities between Riel's followers and the government, climaxing in the famous and final battle at Batoche.

By spring it was all over. Riel surrendered his freedom to the police and was transferred to Regina and charged with high treason. After a two-week trial, he was found guilty and sentenced to hang, despite his lawyers' appeals. On Nov. 16 in 1885 at around 8:30 in the morning Riel was led to the gallows to meet his fate.

Though he was originally branded a traitor to Canada, due to the prevailing prejudices of the time, today Riel is celebrated as a patriot who bravely stood up for his people and his beliefs.

His family home in St. Vital, Manitoba just outside of the French community of Saint-Boniface where he was born and grew up has been designated a national historic site.